Your Genesys Blog Subscription has been confirmed!

Please add genesys@email.genesys.com to your safe sender list to ensure you receive the weekly blog notifications.

Subscribe to our free newsletter and get blog updates in your inbox

Don't Show This Again.

“I knew if I didn’t get out of there, they would kill me. Or I would have to kill somebody.”

Those were my grandfather’s words to me as I interviewed him for my Black History class about his life as a Black man in early 20th century America. The force of those words struck me how intense living in the American South was for him and why he had to leave. He was speaking of the threat of lynching that loomed over every Black man who lived in the United States from the 19th century into the 1960s.

“It was bad in those days, really bad,” he said, grimly staring out the kitchen window and slowly shaking his head.

Born in 1911 in Tutwiler, Mississippi, my grandfather lived in an era and a state notoriously dangerous for a Black man. And being an outspoken, self-confident man, such content of character endangered his life. Lynching was key to oppress and intimidate Black people. He told me it took only a glance, a remark, not stepping off the sidewalk for a white person to pass or simply walking while Black. With impunity and most likely parade-like glee, a group could kidnap, torture and hang you from a tree.

My grandfather was a proud, intelligent man. In a different reality, he would have been able to attend Alcorn State like he always wanted and accomplish his dreams. Oppression, racist hate and this always-present threat on his life would prevent the future he wanted for himself and his family. So, when a friend said, “Bill, let’s go North. We can’t do nothing here,” he decided to leave.

My grandfather was a proud, intelligent man. In a different reality, he would have been able to attend Alcorn State like he always wanted and accomplish his dreams. Oppression, racist hate and this always-present threat on his life would prevent the future he wanted for himself and his family. So, when a friend said, “Bill, let’s go North. We can’t do nothing here,” he decided to leave.

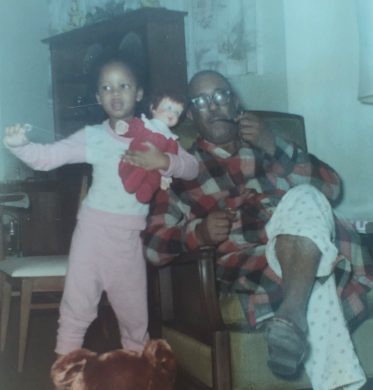

Drawn to opportunities in the North with its foundation in steel and auto industries, Grandad became one of more than 6 million Black men and women who migrated North in what history calls the “Great Migration.” He left my grandmother and their three daughters to find work, build capital and buy a home. Once accomplished, in 1939 he sent money for them to join him in Cleveland. He was able to thrive there, send his daughters to university, secretarial school and enable me to graduate from Northwestern University. It was always embarrassing for me hearing him tell everyone he knew his granddaughter was going to one of the best universities in the world. I can only hope he felt that we both had graduated that June day.

Perhaps you’ve seen pictures of lynching: grainy photos of a Black man dangling from a tree in the 1900s; a Black man in tatters swinging from a tree above an audience of White men, women and sadly, children, grinning and buying souvenirs in the 1920s. In the 1950s,

Emmett Till’s 14-year-old beaten, bloated body lying in his casket, because his mother “…wanted the world to see what they did.” Perhaps you’ve seen video of water blasting from fire hoses and snarling German Shepherds cutting into flesh of peaceful Black protesters in the 1960s or perhaps the dimly illuminated beating of Rodney King in the 1990s.

Say their names: Trayvon. Tamir. Philando. Jordan. Freddie. Sandra. Elijah. Ahmad and on and on.

On May 26, 2020, I watched a 21st century lynching. In color. In broad daylight. On a city street. I witnessed George Floyd writhing on his stomach handcuffed beneath an officer’s knee, struggling to breathe and gasping, “I can’t breathe,” “They’re gonna kill me,” and “Mama.” It’s something I can never unsee or unhear. My stomach churned with outrage and my heart pounded. I wanted to look away, but I felt an obligation to bear witness to this man’s suffering and violation. I watched the officer’s knee pressed on a man’s throat; his smirk; the casualness of his left hand in his pocket while torturing a human being — it was telling me what lynched men saw before they died: “Yeah, I can do this. You can’t touch me.”

I called my husband to my side and said, “I just witnessed a lynching.” It has impacted me in ways I still am unable to fully describe. The only words I can use to express this are: I’m angry, upset, sad and hurt that our humanity means so little we can be erased for nothing. So, I’m reaching out to educate myself more on issues regarding Black people and our history.

I spent Juneteenth reading “Just Mercy” by Bryan Stephenson* for my book club. The focus is about how hard-working people in American can be wrongfully convicted and sit on death row for years; children on death row, and poor women imprisoned due to unfair laws and overly harsh sentences. This book opened my eyes that lynching today can be literal — like Mr. Floyd — and figurative — a system of civil rights denied and abused with brutality because of the color of our skin.

The past seven weeks have been a struggle: the pandemic, authoritarian politics and confronting my own personal reckoning. I’ve remained silent after seeing the countless news stories of Black people mistreated and killed with no response from authorities. I didn’t discuss my resentments with my White friends because it was uncomfortable: that I was offended people who look like me are devalued and disenfranchised, because I (wrongly) felt “less-than” saying so. Although, each time I was infuriated and appalled, I allowed a sad resignation to fade over time as “just another example…” instead of an “Aww, hell no!” moment.

So, what can I do? First and foremost, I will CONTINUE to vote! Too many people of all races, sexes and nationalities have fought and died for this basic right. I can be more diligent in vetting candidates for local office because those positions affect our communities’ schools, policing, justice and housing policies. I can educate myself more on laws passed and the records of my representatives in Washington D.C. I can write to my congresspersons.

Second, I will be silent no more. This is my first blog post… ever. And I choose to speak out about what’s been happening for 400 years. Brutality from those sworn to serve and protect; wrongful convictions by indifferent law enforcement; mass incarceration, overly harsh sentences and uneven laws sanctioned by courts are upheld by my silence. Silence is complicity. I will share my feelings with White friends and colleagues who are interested in understanding my perspective and experience as a Black person. I won’t chase them, but if they ask, I’ll share openly and look forward to any and all their questions.

I was always proud of my grandfather. When he shared his story, I was prouder that he saw injustice and refused to bow to the evils of Jim Crow. In sharing this memory with you — and what it felt to me as a college student then and now — I continue to be proud that he knew his life meant achieving something better and not settling with complacency. He literally saved his life and the futures of my grandmother, mother and aunts. He saved me, too. I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for his courage and conviction to see a threat and do something about it. I can do no less.

Subscribe to our free newsletter and get blog updates in your inbox.